Even More North American Collection

Here's an old favorite. It's a European olive grove by Melba Tucker. It has been in training since 1972 and was donated by Melba's estate in 2000.

I think today's post just might be the best yet when if comes to our series on The North American Collection. If not, it's a close second.

You don't see many American beech bonsai. They are difficult to keep in proportion with leaves that want to get much bigger and internodes that want to keep stretching. Unless you happen to be Julian Adams, who has perfected the somewhat painstaking techniques involved (scroll down for a link to Julian).

This one which is quite impressive, especially given the challenges, was donaled by Fred H. Mies in 2003 and has been in training since 1979.

This lovely Thorny Elaeagnus was gifted to the Museum by Mike Naka in 2004. John Naka originally found it growing on property to be demolished for freeway construction in Southern California. It has been in training since 1960.

This old yamadori California juniper was gifted to the Museum in 2004 by Harry Hirao, one of the great Japanese American bonsai teachers. Harry collected it in the Mojave desert in 1960 and donated it to the museum in 2004.

Harry Hirao (Mr California juniper) from an article in the National Bonsai Foundation newsletter. Even though I never had the privilege of meeting Harry, from what I've heard he was a great teacher, a great human being and a friend to everyone. He first studied bonsai with John Naka. For more on Harry, scroll down for a link to the article.

This wonderfully strange Common privet was originally collected in a cow pasture. It has been in training since 1979 and was donated by Jack Fried in 2010.

Can you imagine being out digging and coming upon a tree like this? It's another California juniper that's no doubt a yamadori (bonsai collected from nature). It has been in training since 1982 and was donated by Sze-ern Kuo in 2012.

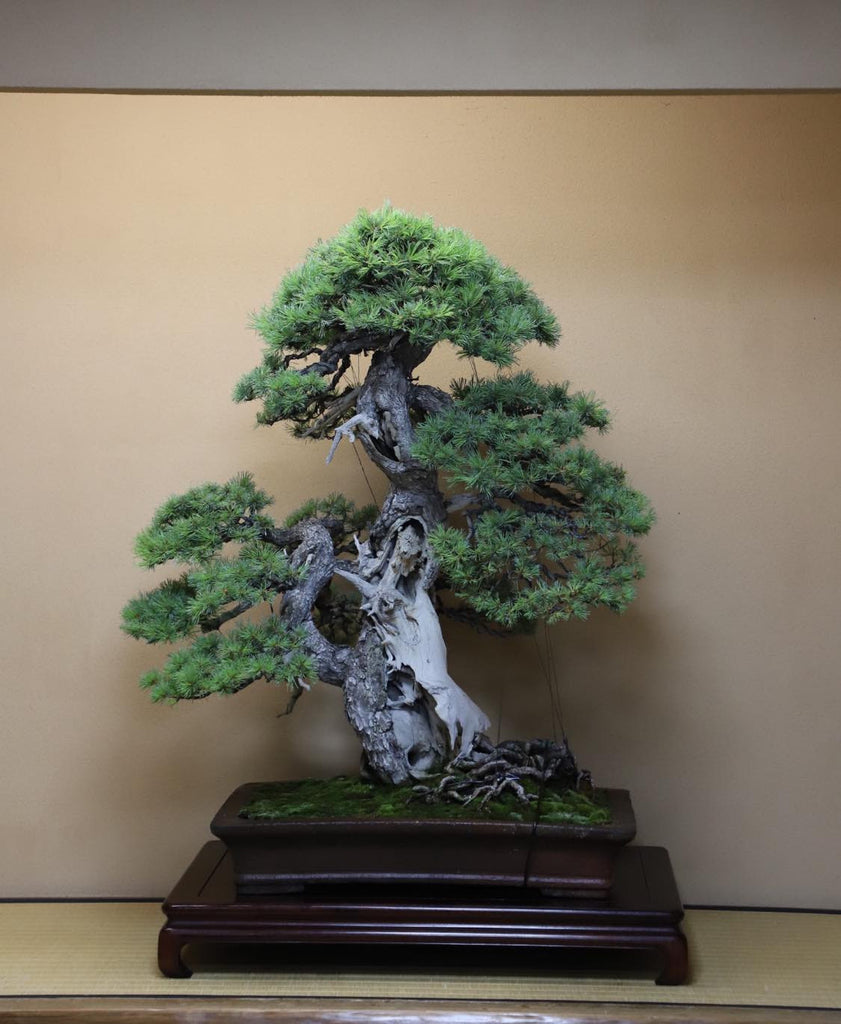

Aha! A tree by Bill Valavanis. It's a Scots pine that Bill donated in 2017 and that he grew and trained since 1880. I don't need to say what a great tree it is, you can see for yourself.

More North American Collection

I've never seen a Japanese garden juniper (J. procumbens 'Nana') with a trunk even half as heavy as this one. In fact I would have guessed that it's grafted, but no word about that and the world is full of surprises anyway. It has been in training since 1975 and was donated to the museum in 1990 by Thomas Tecza.

Because there are so many brilliant bonsai in the North American collection at the our National Bonsai and Penjing Museum, there's no good reason to stop just yet.

I was about to pass on this Crapemyrtle until I noticed that it was gifted by Yugi Yoshimura, one of the very first of the great Japanese bonsai teachers in North America. Mr Yoshimura was also Bill Valavanis' teacher and the second inductee into the National Bonsai Hall of Fame (Bill is the third).

Of further note, this Crapemyrtle was started in Japan from a cutting by Yugi's father Toshiji Yoshimura.

Yugi Yoshimura with Bill Valavanis, a long time ago. Mr Yoshimura died in 1997 and Bill is still going strong.

This root-over-rock Scots pine has been in training since 1972. It was donated by Roland Folse in 1990.

This impressive old Pomegranate has long been one of my favorite Naka trees. It's the great taper and action on the trunk that gets me. It was donated in 1990 by Alice T Naka, John Naka's wife and has been in training since 1963.

What would a North American collection be without a Bald cypress? Before this one became a bonsai in 1987 it was 25 feet tall. Guy Guidry donated it in 1990.

It's not often see so many well developed little Catlin elms (Ulmus parviflora 'Catlin') in one place. And in such a charming and natural representation of a magical forest. Not to mention the perfect slab. The planting has been in training since 1988 and was donated by Susanne Barrymore in 1990.

Here's part of the caption with this planting; "This forest planting was created from cuttings of a mutant contorted Chinese elm developed as a cultivar specifically for use in bonsai."

Aha. Here something you don't see that often unless you live in Texas or surroundings. It's a Cedar elm (sometimes call a Texas cedar elm), and it is an elm (Ulmus) but most definitely not a cedar. In has been in training since 1981 and was donated by Arch Hawkins in 1996.

You might imagine that another tree fell on this Coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia). Or maybe a cow stepped on it. It was donated by John Naka who found it in 1986 on a cattle ranch about 55 miles northwest of Santa Barbara, California.

The North American Collection

John Naka's Goshin, is one of the best known and loved bonsai in the world. The perfect place to start The US National Bonsai and Penjing Museum's North American Collection. The trees are Juniperus chinensis (Chinese junipers) and there are eleven on them. One for each of Mr Naka's grandchildren.

The great John Naka with his Goshin.

This Trident maple was donated by Ted C. Guyger. It has been in training since 1975.

Another Trident, but this time a forest in full fall color. It was donated in 1990 by Brussel Martin of Brussel's Bonsai Nursery in Mississippi.

This full cascade Blue Atlas cedar was a gift by Fred and Ernesta Ballard in 1990.

Another Blue Atlas cedar, but this time the artist is John Naka once again. He gave it the Japanese name Gimpo (Silver Phoenix) because it was once an ugly tree that transformed into a majestic masterpiece.

It wouldn't be a complete North American selection if it didn't have at least one Buttonwood by Mary Madison.

This perfectly serene Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa) was gifted by Mike Uyeno 1990. It has been in training since 1971.

What a unique tree! For starters it resembles a backwards question mark, and that's not the only feature that sets it apart (do you see it?). It was gifted by Jack Douthitt (you guessed it, in 1990).

Stay posted. We've got more great trees from the North American collection in line.

Even More Kobayashi

Look familiar? We featured another iteration a last week. This masterpiece Shimpaku is from Kunia Kobayashi's Shunka-en Bonsai Museum. Its massive flowing deadwood with its single living vein jumps out. As does its strong and compact crown which holds its own in contrast with the sheer power of the deadwood.

A little change of pace. This one is a Diospyros Kaki Japanese persimmon, also from Kunio Kobayashi’s Shunk-en Bonsai Museum.

This muscular old Camellia, full of flowers and buds was taken by Bill Valavanis during a visit to Shunka-en Bonsai Museum back in 2018.

More color. This one looks like a Princess Ppersimmon and the pot looks like it has a story to tell. Photo also courtesy of the omnipresent Bill Valavanis as is the photo just below.

Embrace.

More Kobayashi

Here's a monster (the tree not the man, who happens to be Kunio Kobayashi). Last time we featured some magnificent bonsai brilliance by him and today we've got some more for your enjoyment.

Closeup of some very natural looking deadwood...

...on a very natural looking tree.

Shadow play on what looks like a Shimpaku juniper (or very close cousin).

Kunio Kobayashi posing with an extraordinarily wild looking juniper. It's easy to see which way the wind blows.

Same tree over time.

Here's another Juniper over almost thirty years.

We mentioned last time how so many Japanese bonsai artists love working with deadwood on junipers. There's a good reason for this. Not only do junipers look good with deadwood and take well to carving, but perhaps most importantly juniper deadwood holds up well and can last almost forever with proper care. On most trees deadwood tends to rot and deteriorate faster and requires more care to keep.

Master and apprentice in the workshop.

Koi pond and bridge at Mr Koybayashi's Shunka-en Bonsai Museum.

Can't have a koi pond without koi.

Having fun while removing a large sacrifice branch on a very large tree.

Kobayashi's Bonsai Museum

The great Kunio Kobayashi at work (at play!) with a massive Japanese black pine.

We've got a real treat for you today. It has been a while since we paid a digital visit to Kunio Kobayashi's Shunka-en Bonsai Museum and now that we're doing it, the shear magnificent bonsai (and beyond bonsai) brilliance is overwhelming. Next time we won't wait so long.

This piece of a masterpiece is identified as simply Juniper.

Slanting Japanese black pine.

Another juniper.

The caption with this ancient pine says simply: bless with long life tree.

Most of the great Japanese bonsai artists love junipers and deadwood and Mr. Kobayashi is no exception.

No caption with this, but I think it's safe to say it's a bunjin style pine.

Azalea 'Osakazuki'

Floating Japanese maple leaves. Here's part of the caption: All art starts from nature.

Fin.

A Twin Trunk Hemlock

We've got a rework of a twin trunk Hemlock on a slab by Michael Hagedorn today. Michael is the prime mover behind Crataegus Bonsai and the author of Bonsai Heresy and Post-Dated. Both are considered by many the most entertaining and informative bonsai books around.

In Michael Hagedorn's own words: Before work, January 2023.This Mountain Hemlock was the first tree I put on a nylon slab, back in 2012. We reworked it this week.

After the initial round of work. The right side of this composition has felt foliage-heavy the last few years. The skinny trunks don’t visually support that.

We were considering options of how to lighten the foliage mass on the right to match the airy, left side, when we had a distinguished visitor: Daisaku Nomoto from Japan. He was in town teaching at the new Shohin School here in Portland, headed by Andrew Robson and Jonas Dupuich.

I asked Daisaku what he would do. (This technique I can’t recommend highly enough: when in doubt, wait for a Distinguished Visitor to arrive, who will make the decision for you.) Daisaku recommended removing a couple pads and reducing others, to allow for the airspace that the left side had.

Carmen (my apprentice) and I tweaking the tree for balance. Often when you “think” you’re done, it’s a good time for a break. Step back. Consult a Distinguished Visitor, should any be present. Take photograph. Write some letters. Chase the cat. And then return with renewed purpose, fresh eyes, and covered in cat fur for final tweaks.

The last two photos are correctional in another sense, too. Several recent comments suggested they didn’t believe I existed, having not seen me in recent photos. These last two prove I was around this week, at least. Usually I’m behind the camera.

After the rework. Our choices of branches to remove and others to thin allow for sneak peeks at the right-side trunk. This thinning also reduces the heaviness on that side. Skinny-trunked trees often get overburdened by foliage density. This lightening brings the attention back to the trunks.

When the Hemlock grows out in the spring it should return to “about right” density. This is a tad thin for show. But the thinning in the fall or winter sets the tree up with space to grow.

Masterpiece Penjing

A near perfect penjing, bonsai or whatever you choose to call it. The tree looks like a Shimpaku juniper. Perhaps it was collected in the Mountains of Taiwan where these are abundant.

All of today's photos are from the 4th Zhongguo Feng Penjing Exhibition courtesy of Bill Valavanis. Bill posted them on his Welcome to My Bonsai World blog, one of our favorite destinations.

Literati style Penjing. Literati dates back hundreds of years to when Chinese poets, artists and calligraphers were called Literati. Once you know this association with calligraphy, it's easy enough to see why (the Japanese word for this style is Bunjin - literati and bunjin are often used interchangeably by English speaking bonsai enthusiasts).

I might be reluctant to call this one literati. It has the tall thin trunk with most of the branching toward the top that we associate with literati, but the abundance of rich foliage speaks of a life that's may be too soft for literati, which are typically associated with the kind of hardship you might find on a cold, high mountain cliff or other inhospitable environs.

Halloween tree. With a little imagination it might be scary. No variety is given.

Bonsai candelabra with deadwood.

This elegant Princess persimmon is Bill's favorite from the show.

Monster Trees

Here's a rather impressive multi-tree Siberian elm. I count 31 trunks.

Today we've got some monster and less than monster penjing from a site called LingNan PenJing. Penjing is bonsai that is commonly found in China and Southeast Asia (especially in Vietnam where bonsai is everywhere). It is not nearly as popular in North America and much of the West, where most bonsai are influenced by the Japanese tradition. Still, the best of penjing is spectacular, though it might take some getting used to.

Just in case you think we're exaggerating when we say monster Penjing.

Still a penjing, but a little closer to Japanese influenced styling.

This type tray is common in penjng forests and other landscape plantings. There are no drain holes by the way. This does not present a drainage problem if you know what you're doing.

This type tree-rock combination is fairly common in penjing. Little human and other figurines are also common in penjing. This one works to perfection by instantly creating the illusion size and space.

If this were in Japan I think it might qualify as bunjin (though the trunk is a little heavy). In China they are called Literati (Wenjen). This term comes from caligraphy and dates back at least to Han Shan and the old Cold Mountain masters.

One more 'monster' shot from LingNan PenJing